A Comprehensive Guide to Guitar Effects and Signal Processing

Guitar effects and signal processing have been an essential part of creating unique and inspiring sounds for guitarists across genres for decades. From the early days of analog effects to the modern digital realm, the evolution of guitar effects has been marked by groundbreaking innovations and the continuous pursuit of sonic perfection.

Sound engineers have always aimed to create guitar amplifiers that deliver pure and undistorted sound. Over time, they’ve also crafted devices that drastically alter the guitar’s sound.

With effects gear, a guitar can mimic the sounds of a piano, organ, saxophone, circular saw, jet fighter, or even produce completely unnatural sounds.

A guitarist can enhance their sound with an effects unit, provided they know how to use it properly. However, cranking it up without skill can turn even mediocre guitar play into a disaster.

The gap between legends like Jimi Hendrix, Mark Knopfler, or Slash and an average guitarist isn’t just about their effects pedals. While distortion can create a crisp, edgy sound, it can also result in a chaotic mess where nothing sounds distinct, regardless of playing skill.

Ultimately, effects gear can’t make up for a lack of talent or technique.

In this post, we will take an in-depth look at the history and development of guitar effects, explore the different types of effects available, and discuss how they have shaped the sound of popular music through the years.

Table of Contents

A Brief History of Guitar Effects

The Early Days (1940s – 1960s)

The origins of guitar effects can be traced back to the 1940s when musicians began experimenting with different ways to alter their guitar sounds. These early effects were primarily based on vacuum tube technology, which was also used in amplifiers and radios at the time.

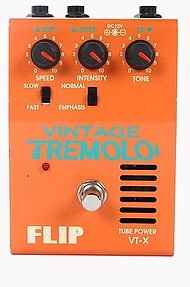

One of the first widely used guitar effects was the tremolo, which created a pulsating modulation in volume. This effect was initially built into tube amplifiers, such as the Fender Tremolux and the Vox AC15. Later on, standalone tremolo units, like the DeArmond Tremolo Control, became available, allowing guitarists to achieve this effect regardless of their amplifier.

In the late 1950s, the first standalone guitar effects pedals were introduced. The Maestro Fuzz-Tone, released in 1962, was one of the earliest fuzz pedals, providing a distorted, sustain-rich sound that was popularized by The Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards in their hit song “Satisfaction.”

The Golden Age (1970s – 1980s)

The 1970s and 1980s marked the golden age of guitar effects, with countless new devices being introduced to the market. One of the most iconic pedals of this era was the Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi, a fuzz/distortion pedal that helped define the sound of guitarists like David Gilmour, Billy Corgan, and J Mascis.

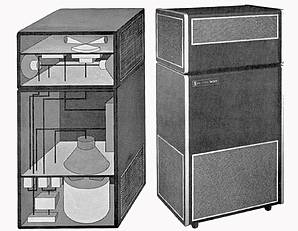

During this period, companies such as MXR, Boss, and Ibanez were also founded, and they introduced many classic effects, such as the MXR Phase 90, the Boss DS-1 Distortion, and the Ibanez Tube Screamer. Multi-effects units, like the Roland GR-500 Guitar Synthesizer, also emerged, allowing guitarists to access a wide range of effects in a single device.

The advent of digital technology in the 1980s brought about a new wave of innovation in guitar effects. Devices like the Eventide H3000 Harmonizer and the Lexicon PCM42 Digital Delay revolutionized the world of guitar effects by offering unprecedented levels of control, sound quality, and versatility.

Types of Guitar Effects

Tremolo

A tremolo circuit is an amplitude modulator that creates subtle volume variations in the signal. This amplitude modulation is controlled by a knob often labeled ‘depth’ or ‘intensity,’ allowing sounds to range from gentle wave-like oscillations to rapid echo-like repeats. The time between the loudest moments of the sound is adjusted with knobs marked ‘speed,’ ‘frequency,’ or ‘rate,’ usually within a range of about 2 to 8 cycles per second (cps).

Many tremolo units use a field-effect transistor (FET), though some operate using a photocell or light-dependent resistor (LDR). Because the effects of tremolo and vibrato are similar, they’re often confused. Additionally, the term ‘tremolo arm’ is sometimes incorrectly used to describe the vibrato arm on guitars like the Stratocaster; the correct terms are ‘vibrato arm’ or ‘whammy bar.’

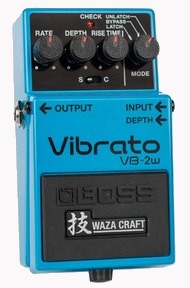

Vibrato

Vibrato circuits vary the pitch (not the volume) of the signal, producing a sound that fluctuates up and down. The effect and controls are similar to those of a tremolo, but with vibrato, you can extend the intervals by adding extra resistance or replacing the potentiometer with one of a higher resistance value.

Reverberation

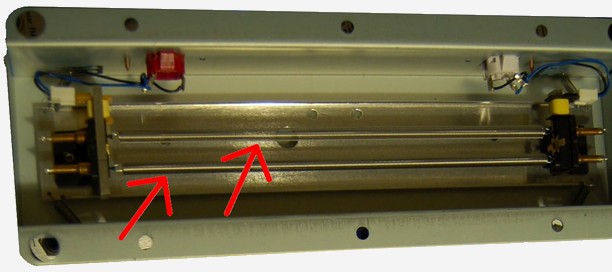

Mechanical reverberation devices utilize two metal springs to carry the electric signal. The signal is converted into a mechanical pulse, travels through the springs, and is then converted back into an electrical signal. One metal spring delays the signal by about 29 milliseconds, while the other delays it by 32 to 38 milliseconds. Part of the signal bypasses the springs and is sent directly to the amplifier, creating the initial sound you hear, followed by the delayed effects from the springs. This can produce an echo effect that gradually fades.

Reverberation can be likened to rapid, sequential echoes blending together, with the ‘depth’ knob adjusting the balance between the direct signal and the spring-affected signal. At lower settings, it mimics the acoustics of a concert hall; at higher settings, it sounds like a long tunnel. It’s important to keep amplifiers with mechanical reverbs or any reverberation device secure to avoid loud noises from springs clashing together due to movement. Most modern reverb units are entirely electronic, eliminating this issue.

Wah-Wah

The wah-wah pedal, placed on the floor, acts essentially as a tone control, altering the sound from high to low and back again. To effectively use a wah-wah, you need to adjust your playing style. It requires optimal coordination between your hands and feet to achieve the desired effect.

Notable examples of wah-wah usage include Eric Clapton’s “White Room” with Cream, Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile,” and “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” by the Temptations, where the guitar was played by Melvin M. Ragin, better known as Wah Wah Watson. Most wah-wah pedals are durable and unlikely to break easily. For the best results, move the pedal slowly to allow the sound to transition smoothly from low to middle to high, and vice versa.

Distortion, Overdrive, and Fuzz

A fuzz, or ‘distortion‘ pedal, is a device that creates effects ranging from an overdriven amplifier to a continuous, buzzing sound. It transforms the guitar’s signal from a smooth wave into a jagged one, resulting in a distorted sound. The device is housed in a metal box and connects between the guitar and the amplifier, with a foot switch to toggle it on and off. Fuzz pedals typically have two controls: one for volume and one for the intensity of the effect, often labeled as ‘fuzz,’ ‘distortion,’ or another synonym. However, some models come with additional controls.

The intensity control is crucial. Some fuzz pedals have a limited range, effectively acting as an on/off switch for the effect. With fuzz, you gain more sustain, and some models also allow you to produce a distorted staccato sound. There are also versions that provide sustain without adding distortion, ensuring each note remains clear. Prominent fuzz brands include Foxx, Woods, Electro-Harmonix, MXR, Vox, Ampeg, Ibanez, Fender, Maestro, and Kent, among others.

Many guitarists prefer the natural distortion achieved by cranking an amplifier to its maximum, although this is not recommended. Doing so can overload the amplifier’s tubes or transistors and the speakers, causing significant damage or even blowing them out.

Echo

The variety of echo units, devices that replicate sounds as repeats, is vast. An older but still commonly used type operates with a looped tape, a recording head, and a playback head (Tape Echo). The first head records the signal, and the second plays it back, with the first head recording the signal again to create an echo.

Additional playback heads can provide more complex options. Adjusting the distance between the heads changes the delay; a shorter distance, and thus shorter delay interval, can produce a reverberation effect. Adjusting the tape speed can also produce various effects. Tape echoes require regular maintenance: the heads need frequent cleaning, and the looped tape must be replaced as it wears out to maintain sound quality. Notable brands of tape echo devices include Dynacord and Roland.

Electrostatic units, which operate without tape and use a magnetic disc or drum with six heads, offer expanded possibilities and high reliability. However, the most common echo devices now are fully electronic, without moving parts, using digital technology to create spectacular effects. For instance, they can add extra tones that differ from the original.

Compressor

A guitar has a wide dynamic range, from extremely soft to very loud chords, which can pose challenges for an amplifier. If an amp is set to amplify soft tones well, louder tones might distort. Conversely, setting the amp to handle loud tones can make softer ones barely audible. This is particularly problematic for recordings, as recorders have their own dynamic limitations. A compressor moderates high peaks and boosts low volumes, eliminating extreme output differences.

When it encounters a loud, sharp tone, it softens the peak and gradually increases amplification, allowing the tone to sustain longer without fading. Properly adjusted, a compressor can provide more sustain with minimal or no distortion, leading to a more consistent signal where extremes are smoothed out. This generally allows for a louder signal, making subtle nuances that might otherwise be lost audible. Proper compressor adjustment is crucial to minimize noise.

Tone Booster

These gadgets enhance specific frequencies to shape the sound of your instrument. You can find bass boosters, treble boosters, and even devices that amplify both high and low frequencies. Boosters can either focus on a narrow frequency range or enhance all tones above or below a set threshold.

The former targets a specific spot on the frequency curve, while the latter boosts everything from a chosen point, creating a rising or falling effect across the spectrum.

Talk Box

Also known as a Voice Box, the Talk Box is a device placed on the floor that houses a small amplifier and speaker. Your guitar connects to this box, which then feeds into your guitar amp. Instead of using a conventional speaker cone, the sound travels through a plastic tube.

This tube, often attached to a horn driver, extends to your mouth, where you can modulate the sound by changing the shape of your mouth and vocalizing. The end of the tube is positioned near a microphone, usually one that’s part of the PA system, allowing the modified sound to be amplified and heard.

Envelope Modifiers

Envelope modifiers affect the shape of a sound wave, including its attack, sustain, and decay. Thanks to synthesizer technology, it’s possible to use external envelope modifiers that introduce various effects. A common application is the electronic wah-wah effect, where the guitar signal is transformed into a voltage that triggers a filter.

The intensity of your strumming controls the filtering effect, creating a dynamic response as the note fades. The result is a transformation of the guitar’s sound into expressive “wah,” “wow,” “bow,” “quack,” and “tweety” sounds. Notable envelope modifiers include the Funk Machine by Seamoon and the Mutron III, famously used by Stevie Wonder, among others.

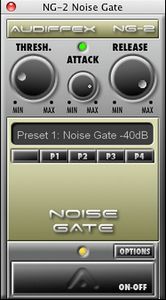

Noise Gates

Sub sounds can be caused by everything, from amplifiers, instruments, cords, effect units etc. Noise gates act like audio filters, allowing signals above a certain level to pass while blocking those below a certain threshold. This ensures that even the softest desired tones come through louder than any unwanted background noise. You adjust the threshold so the softest sounds you want are audible, but anything quieter is silenced.

Setting the threshold correctly is crucial; if it’s too high, noise persists, and if too low, it may block quieter musical passages.

Pre Amplifiers

Using a preamplifier can boost a guitar’s signal before it reaches the main amplifier, reducing noise amplification. A preamp can also intentionally overdrive an amp for a distorted sound, similar to a fuzz or scrambler. However, unlike fuzz, which generates distortion on its own, a preamplifier enhances signal clarity and, if set high enough, can cause the amplifier to distort.

For those looking for a scrambler effect, trying an external preamp might be beneficial. Some guitars have built-in amplifiers for added versatility.

Leslies

The Leslie speaker, known for its pulsating vibrato, utilizes the Doppler Effect, where sound pitch changes based on the movement of the sound source relative to the listener. As the Leslie’s speaker rotates, the sound seems higher when directed towards the listener and lower when moving away, creating a phase shift and a rich, complex sound due to the varying harmonic structures.

Phase in audio refers to the alignment of sound waves. When in sync, they amplify the sound; when perfectly out of sync, they cancel each other out, resulting in silence. Natural phase differences create various sound patterns by selectively canceling or amplifying certain frequencies, often visualized in graphs showing how these interactions affect sound. A filter that creates such effects is known as a “bridge filter.” While the Leslie is famously paired with the Hammond organ, it also produces fantastic effects with the guitar, adding a unique dimension to its sound.

Phaser

Originally inspired by the electronic imitation of the Leslie’s Doppler Effect, the phaser has evolved to produce its unique sound, reminiscent of wind or a jet engine. A phaser uses voltage-controlled filters to alter the phase of incoming signals. These changes in phase can cancel out or amplify certain waves when mixed, depending on their relationship. The inclusion of multiple filters means a richer, deeper effect.

An oscillator modulates across the bandwidth, shifting the point of phase cancellation, creating a sound similar to a strong wind. The speed of this modulation, known as ‘sweep,’ can be adjusted with a ‘speed’ knob, preset switches, or a pedal. Some phasers also feed part of the signal back into the device, enhancing the complexity of the harmonic structure and emphasizing the phasing effect even further.

Flanger

Flanging traces its origins to a studio technique from the late 1950s involving two synchronized tape recorders playing the same recording. By pressing on the tape reel’s flange, one recorder would slightly desynchronize, creating a phase shift.

An electronic flanger replicates this effect using an analog delay line. Flanging produces a sound more closely related to studio phasing than to the distinct sound of a phaser, maintaining constant sustain. The more complex the signal, the more pronounced the flanging effect.

Ring Modulator

A ring modulator is an intricate device that generates bell-like harmonic tones, with adjustable intensity. Playing a lick on the guitar can produce harmonics that move in the same or opposite direction.

The device can be adjusted to highlight just the tonic or synthesized overtones, offering a range of natural variations. Ring modulators create spacey, dissonant sounds, challenging the player with their complexity.

Consoles

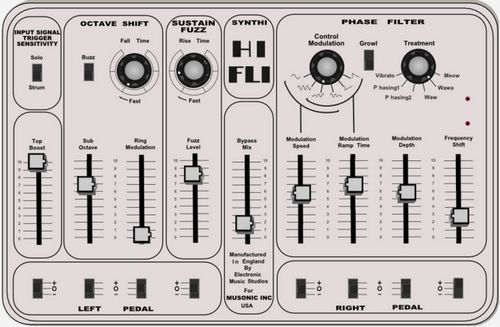

With the rise of electronic music, compact synthesizer units have become available for guitarists. One of the pioneers was the HiFli from EMS, equipped with two pedals and capable of producing various effects like fuzz, sustain, phase, frequency modulation, wah-wah, and vibrato.

Other comprehensive units include the G-2 Guitar System from Maestro and the Mode Synthesizer from BCM. Leading brands in music equipment also offer their console systems, providing guitarists with a wide array of sound-shaping possibilities.

Theremin

Though not directly related to guitar effects, the Theremin is a unique electronic musical instrument that deserves mention. Invented by Russian professor and musician Leon Theremin in 1920, it consists of two electrically charged antennas connected to a high-frequency circuit. Players control the instrument without physical contact, manipulating their hands in the air near the antennas to adjust pitch and volume, utilizing the electrical capacitance of the human body.

The Theremin is capable of producing ethereal, voice-like sounds and can mimic woodwinds, strings, and even the human voice. The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” features the Theremin, showcasing its distinctive sound. It has also been used in film scores, notably in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1947 movie “Spellbound,” to create eerie and suspenseful music.

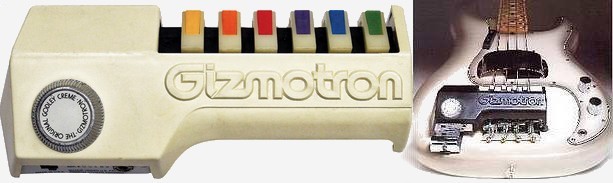

Gizmotron

Invented by Lol Creme and Kevin Godley of 10CC, the Gizmotron attaches to a guitar’s bridge. It contains wheels for each string, which, when activated by pressing buttons on the device, rub against the strings to produce sounds akin to a cello.

The Gizmotron allows for regular plucking or strumming in conjunction with its unique sound. It’s featured in 10CC’s “I’m Not in Love” and on the albums “Consequences” and “L” by Godley & Creme, demonstrating its capabilities.

Octave Dividers and Octave Multipliers

Octave dividers add notes one or two octaves lower than the played note, simulating the effect of a bassist and guitarist playing in unison. However, these devices may sometimes trigger harmonics instead of the fundamental note or produce a distorted added tone. They can be sensitive to subtle playing dynamics and may not handle chord play well, resulting in indistinct sounds.

Despite their limitations, octave dividers can create interesting effects, especially with monophonic signals like wind or brass instruments. Conversely, octave multipliers add a higher octave, enriching the sound spectrum with higher pitches.

Linking of Effect Equipment

When connecting effects units, the sequence can significantly impact the overall sound. Starting with the preamplifier and then the compressor enhances the output level without introducing excessive noise.

Fuzz or ring modulators should be set up parallel to each other, allowing you to choose between them without adding unnecessary links in the chain, which could degrade signal quality. Next, place the envelope modifier and wah-wah side by side to maintain a stronger signal, but be mindful that activating fuzz or compression may alter the envelope modifier’s response.

A phaser works best at the end of the chain, as it processes complex harmonic signals most effectively. Lastly, position the echo and volume pedal, with the pedal after the echo to maintain echo effects even when muting the signal, or before the echo to control its level along with the overall signal. Utilizing a volume pedal helps balance the level differences that various effects can introduce.

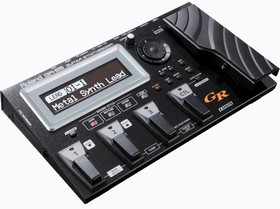

Guitar Synthesizer

Early guitar synthesizers struggled with the jagged guitar signal and failed to capture dynamic differences, losing some guitar essence. Modern systems integrate synthesizer capabilities without compromising the guitar’s core sound. These include guitars with special circuits, interface units, and comprehensive systems.

Synthesizers typically suit solo or single-string play over chord accompaniment, as polyphonic units handle chords well but monophonic ones may lose chordal harmony or only output the last played note. Using arpeggio technique can mitigate this issue.

An interface unit converts the guitar’s analog signal into a digital format suitable for synthesizers, such as the Slave Driver by Bob Easton’s 360 Systems, featuring a pitch-to-voltage converter and an envelope follower for pitch and loudness conversion, respectively.

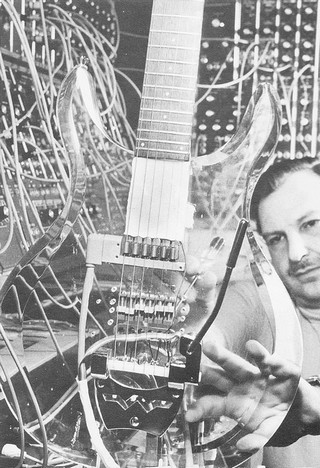

Walter Sear’s polyphonic guitar synthesizer, using a ‘Dan Armstrong’ plexiglass guitar and a synthesizer unit, allows for individual string effect settings, enabling rich harmonic structures.

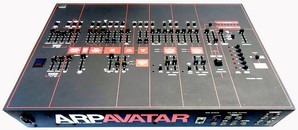

ARP Instruments’ Avatar guitar synthesizer from 1977 offers extensive effects through individual string sensitivity adjustment and components like VCOs, VCFs, and envelope modifiers. This unit was notably used by Pete Townshend. The Hagström Patch 2000 system, built into the guitar’s neck, activates electronics through string and fret contact, available for both bass and guitar.

The Impact of Guitar Effects on Music

Guitar effects have played a crucial role in shaping the sound of music throughout history. They have enabled guitarists to push the boundaries of their instrument, carving out new sonic territories and defining the character of countless songs and genres. From the psychedelic rock of the 1960s, which relied heavily on fuzz, phaser, and delay effects, to the heavily distorted and processed sounds of 1990s grunge and alternative rock, guitar effects have been at the forefront of musical creativity.

Today, guitar effects continue to evolve, with digital modeling and advanced signal processing techniques offering even greater possibilities for sonic exploration and experimentation. Modern multi-effects processors, like the Line 6 Helix and the Fractal Audio Axe-Fx, combine a vast array of high-quality digital effects with amp modeling and advanced routing options, allowing guitarists to craft complex, fully customizable tones with ease.

Furthermore, the rise of software-based effects and digital audio workstations (DAWs) has made it possible to process and manipulate guitar signals in ways that were once unimaginable.

In recent years, the boutique pedal market has also seen tremendous growth, with small, independent manufacturers crafting unique and innovative effects that cater to the specific needs and tastes of individual guitarists. From hand-wired analog circuits to cutting-edge digital processors, the diversity and quality of guitar effects available today are unparalleled.

VST Plugins for Guitar Effects

In addition to hardware-based effects, Virtual Studio Technology (VST) plugins have become an increasingly popular option for processing and manipulating guitar signals in a digital environment. VST plugins are software-based effects that can be used within digital audio workstations (DAWs) like Pro Tools, Ableton Live, and Logic Pro, offering a wide range of processing options for both recording and live performance.

Some of the most popular VST plugins for guitar effects include:

- AmpliTube by IK Multimedia: AmpliTube is a comprehensive guitar and bass tone studio, featuring a vast array of amp models, cabinets, stompboxes, and rack effects, as well as advanced tone-shaping and routing options.

- Guitar Rig by Native Instruments: Guitar Rig is a versatile guitar effects and amp modeling software that includes a wide range of high-quality digital effects, amp models, cabinets, and microphones, allowing users to create an almost infinite variety of tones.

- BIAS FX by Positive Grid: BIAS FX is a powerful guitar effects and amp modeling software that combines realistic amp models with a comprehensive selection of stompboxes and studio rack effects, as well as advanced signal routing capabilities.

- S-Gear by Scuffham Amps: S-Gear is a boutique guitar amp modeling software that focuses on delivering high-quality, realistic amp tones and a simple, intuitive user interface.

These VST plugins offer numerous advantages over traditional hardware effects, such as the ability to automate effect parameters, integrate with other software instruments, and quickly recall and switch between different effect chains and settings. Moreover, VST plugins can often be more cost-effective than their hardware counterparts, making them an attractive option for guitarists on a budget or those looking to minimize their physical gear.

Conclusion

From their early beginnings with vacuum tube-based effects to modern digital processors and VST plugins, guitar effects have come a long way, significantly impacting the sound and development of music. By exploring the history, types, and impact of guitar effects we can better appreciate the role these tools have played in defining the sound of countless iconic songs. And the guitar effects will undoubtedly continue to shape the sound and direction of music in the future.